Past administrations have used their own evaluative data to justify funding cuts. To counter this, afterschool funding recipients must increase measurement of program effectiveness. Afterschool programs need specific and solid data, from internal and external evaluators, to prove the strong need for funding that positively affects students. With myriad factors affecting students, programs need to produce compelling evaluation data that supports continued and increased funding.

In spring 2017, the Trump administration claimed there is no evidence that afterschool programs benefit students academically. This "no evidence" myth began 15 years ago, when a two-year, federally commissioned 21st Century Community Learning Centers evaluation found no impact on homework completion or academic outcomes. First-year findings were used to justify President George W. Bush's recommended 40 percent cut to 21st CCLC funding in 2004, though the study examined student outcomes at only 26 programs in 12 districts.

Afterschool program opponents publicized the study as experimental research since students were randomly assigned to programs from a waiting list. Researchers and educators criticized the study for its questionable methods and warned against generalizing its findings or using them as a basis for policy decisions.

Critics questioned the study for ignoring differences in the characteristics of afterschool participants and the comparison group, especially differences in prior academic performance. They criticized the study for low dosage (attendance) requirements and the fact that many comparison students actually participated in afterschool programs, though not funded by 21st CCLC. Some programs studied were not meant to provide academic intervention and were never intended to affect the outcomes measured—homework completion, grades and standardized test scores.

Since this study was published, a growing body of research has demonstrated that afterschool programs can and do affect student academic performance when treatment and groups are carefully matched, comparison samples sizes are adequate, and important variables such as program quality, intention and dosage (participation levels) are properly accounted for.

To dispel myths about afterschool program ineffectiveness, practitioners must do a better job of internal and external program evaluation. Evaluation or self-assessment is the first step of the Continuous Quality Improvement process. Data must be collected and used to plan for improvement. When planning effective afterschool programming, a goal or intended outcome must always be specified. Evaluation is used to determine whether that goal has been accomplished, to what extent, or what needs to be modified in the plan to achieve success. The process of evaluating—whether collecting data through surveys, observation or focus groups—also helps determine the degree of fidelity to which programs are executed. This data can be important for securing alternate income streams. When applying for funding sources, evaluative data can be useful for showing programming effectiveness.

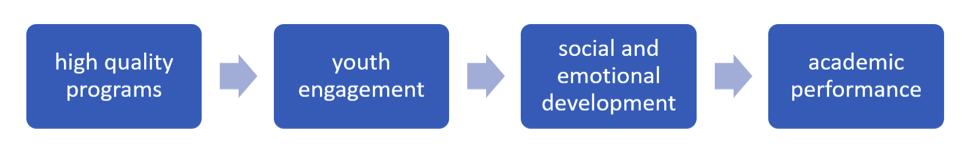

Evaluation of Beyond the Bell Branch afterschool programs in the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) is designed to produce data that will attract funding and influence policymakers. Beyond the Bell's evaluation model is based on a Theory of Change, suggesting adequate participation in high-quality programs results in socio-emotional skill development, a mediator of academic achievement. Participation is measured in terms of intensity (days attended per school year), duration (years attended) and breadth (activities variety).

Program quality is measured objectively and subjectively. Objectively, it is measured by activity observations conducted by internal district monitors and an external evaluator using a rubric based on the Learning in After School and Summer Principals. Subjectively, it is measured by conducting site coordinator interviews, principal interviews, student focus groups and student feedback surveys, all aligned to the Quality Standards for Expanded Learning in California.

Research-validated scales are designed to measure specific socio-emotional skills associated with academic achievement. These skills include school connectedness, self-management, self-efficacy, growth mindset and social awareness.

Finally, academic achievement is measured by performance on standardized test scores, grades and percentage of credits earned toward high school graduation.

Beyond the Bell Branch's Theory of Change

Beyond the Bell Branch's evaluation model is one example of measuring program quality and effectiveness. To influence policymakers and silence the "no evidence" myth, similar efforts must be made by afterschool consortiums nationwide.

Afterschool programs make a difference in the lives of students. It is up to us to prove it.

Written by: Stephen Price, Ed.D., ERC lead evaluation consultant, Beyond the Bell LAUSD external evaluator, and Robert Diaz, Field Coordinator, Beyond the Bell LAUSD.

This article originally appeared in AfterSchool Today.